Measure Two Hundred Times, Tweak Twice

My buddy Pure.Krome stopped by the JabbR nerd chat with a question.

With this code, would a string be created each time the response was generated?

httpResponse.Headers["Cache-Control"] = $"public,max-age={seconds},must-revalidate";David Wengier helpfully provided an answer (yes), and why (a bling-string is just a string.Format() call when it's converted to IL). But, in TRUE NERD FASHION, we took things to the extreme with some helpful and not-helpful alternatives.

Mr. Wengier also has a talk on pragmatic performance that is worth the watch and inspired me to sit down and play with BenchmarkDotNet for the first time.

BenchmarkDotNet is a wonderful tool for micro-benchmarking. When you have a small bit of code and you want to know if one option is better or worse than another, you need a miro-benchmarking tool. It will warm your environment to establish a baseline. Then it will run though a bunch of iterations for you and present a cleaner picture than if you put a timer on each end yourself.

Below, I set up a .NET Core console app, create a class to hold the benchmarks I want to compare, and then tell the BenchmarkRunner to go to town. By default, the output will be sent to the console window.

[CoreJob]

public class Strings

{

[Benchmark(Baseline = true)]

[ArgumentsSource(nameof(PassingInts))]

public string BlingString(int seconds) => $"public,max-age={seconds},must-revalidate";

}

public IEnumerable<int> PassingInts()

{

yield return 60;

yield return 60 * 60;

yield return 60 * 60 * 24;

}

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

var summary = BenchmarkRunner.Run<Strings>();

}

}And, spoiler alert, the BlingString(seconds) method is not speedy. But, it's not horrible. I'm going to throw my pragmatic hat in the bushes and come up with some alternatives. Then I'll order a shiny, new pragmatic hat and discuss trade-offs.

First, the easy alternative. If we want execution speed, then let's just hard-code something in. Everything gets cached for an hour.

[Benchmark]

public string Literal() => "public,max-age=3600,must-revalidate";If BlingString is our skateboard, then Literal() is the super-charged sport bike. There is no computation. BenchmarkDotNet is confused why it's here.

Strings.Literal: Core -> The method duration is indistinguishable from the empty method durationThat's interesting but... well, only until one of your teammates uses your cache header function when they want to cache a critical lookup for just a second. Then your high-frequency trading app makes decisions on stale data. The investors lose millions. And you swear you'll never use C# again.

So, now we know that literals are fast. And, we know that string.Format() (our bling string) is slow. If we could just cache strings we've returned before...

It turns out, in fact, that we can do just that.

One of the collection objects in .NET is the ConcurrentDictionary. It's thread-safe (well, enough for our usage) and, as importantly, it has a GetOrAdd method we can use

TValue GetOrAdd(TKey key, Func<TKey, TValue> valueFactory);If a given key exists, then the value is returned.

If the key does not exist, then the Func is called to generate the value. The value is then added to the dictionary and returned. Broadly, this means we can store our cached strings and generate new ones only when needed.

private ConcurrentDictionary<int, string> LittleShopOfHorrors = new ConcurrentDictionary<int, string>();

[Benchmark]

[ArgumentsSource(nameof(PassingInts))]

public string LookupDictionary(int seconds) =>

LittleShopOfHorrors.GetOrAdd(seconds, s => $"public,max-age={s},must-revalidate");But, this has a glaring problem that Aaron Dandy pointed out "dictionaries fill up". That is, there's no limit to how big our dictionary can grow. Other developers, intentionally (adversarial) or not, might leave you with a 2GB dictionary full of unused values.

But, this part of the journey is to keep some brainstorming ideas going. We don't have our pragmatic hat on so we don't care about memory!

On to a couple of more elegant ideas proposed by David...

First, if we're fairly sure that we will often see many requests for the same value at once, we can implement a poor cache. Just track what we've seen last and use that if it matches.

private int _lastSeconds = 3600;

private string _lastHeader = "public,max-age=3600,must-revalidate";

[Benchmark()]

[ArgumentsSource(nameof(PassingInts))]

public string LastCache(int seconds)

{

if (_lastSeconds != seconds)

{

_lastSeconds = seconds;

_lastHeader = $"public,max-age={seconds},must-revalidate";

}

return _lastHeader;

}This retains the flexibility of working for any number of seconds passed in while betting on most calls using the same value.

The next option is to just take all but a couple options off of the table. We can use an enum to control what is returned.

public enum CacheLengths

{

Short = 60,

Medium = 60 * 60,

Long = 60 * 60 * 24

}

[Benchmark]

[ArgumentsSource(nameof(PassingEnums))]

public string LiteralByChoice(CacheLengths cacheLength)

{

switch (cacheLength)

{

case CacheLengths.Short:

return "public,max-age=60,must-revalidate";

case CacheLengths.Medium:

return "public,max-age=3600,must-revalidate";

case CacheLengths.Long:

return "public,max-age=86400,must-revalidate";

default:

return "public,max-age=0";

}

}Now, obviously, this is very inflexible. But, on the other hand, it allows the original author to provide a clearer indication of what the impact of a given value is.

Last, I came up with what I feel is a more esoteric option. I learned a lot about some parts of the framework that I didn't know before. I can keep this knowledge filed away in case I need it in the future. And, of course, we're not going to limit ourselves until we see what the runtime characteristics are.

private const int Entries = 20;

private const int StepSize = 60;

private static readonly int[] _acceptableSeconds =

Enumerable.Range(1, Entries).Select(seconds => seconds * StepSize).ToArray();

private static readonly string[] _fuckYouImATrain =

_acceptableSeconds.Select(seconds => $"public,max-age={seconds},must-revalidate").ToArray();

[Benchmark]

[ArgumentsSource(nameof(PassingInts))]

public string FindNearest(int seconds)

{

var idx = Array.BinarySearch(_acceptableSeconds, RoundToNearest(seconds, StepSize));

if (idx > -1)

return _fuckYouImATrain[idx];

return ~idx < Entries ? _fuckYouImATrain[~idx] : _fuckYouImATrain[Entries - 1];

}We create some acceptable values for seconds. And then we create a string array of cache headers generated from those acceptable values.

When FindNearest(seconds) is called, we want to find the closest matching header. We know that we store strings generated in 60 second increments. So, if FindNearest(50), FindNearest(60), or FindNearest(59) is called, then we want to find the nearest match to 60 (in this case).

This code is, honestly, a mess from top to bottom:

- It relies on keys and values being the same length and in the same order.

- The returned value does not follow the principal of least surprise because there's no obviously correlation between what you pass in and what you receive back (better naming would help a little).

- From a maintenance standpoint, you'll need to remember what operator

~is each time you read the code; - you'll have to know why you're using either the index or the XORed compliment of the index

- and you'll have to think about bounds checking.

But, if the speed is there then maybe... maybe... it's worth it.

Let's put it all together (gist here) and see what those numbers look like.

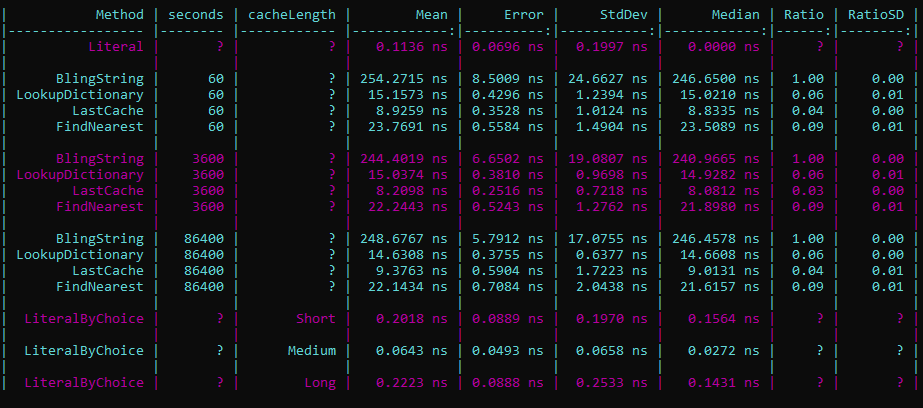

A look at the results will tell us that, by far, the bling string approach is the worst with a mean time of about 250 nanoseconds per call.

Our enum option is the best contender if we can live with the constraints while the the simple cache approach is perfect if we'll often use the same value in subsequent calls (it trends towards the bling string performance the less often that's true).

The lookup dictionary is next fastest while our binary search is slow enough that it hardly seems worth the trouble. This is because search time for the dictionary is an O(1) operation while the binary search is, on average, O(log n). (Thanks Wikipedia!)

So, pragmatic hat back on. What's the best option? That depends! Look at that, after reading all the way to here, I pull out a trite catchphrase. This is where we need to understand our system. We don't care about optimizing the 97% that doesn't matter; we need to apply ourselves to the 3% that does.

If this method is called on every single HTTP request, but it's an internal app that gets called 1000 a day, then who cares! Leave the bling string in place.

Or, if this is only called when an image is requested from blob storage and the cache time is an hour, then maybe just hard-code it and be done.

On the other hand, if this is part of some critical infrastructure where saving milliseconds will net you a comfortable end-of-year bonus, then it's time to dig in and make some harder choices that depend on understanding your system.

When we optimize code, we have to keep mutiple audiences in mind. There's the callers of our code. Which design choice keeps the API straightforward and unsurprising? There's future maintenance devs (including yourself after you've forgotten the reasoning behind your original implementation). Which change makes the code straightforward? What can we do to minimize breaking logic changes? And, of course, the runtime. Which change has a positive impact on execution time? Which change is least likely to have unintended runtime consequences if misused?

Lots of questions but no answers. But, with a solid handle on writing small benchmarks to evaluate options, you'll be better equiped to make choices within the scope of the applications that you write and maintain.